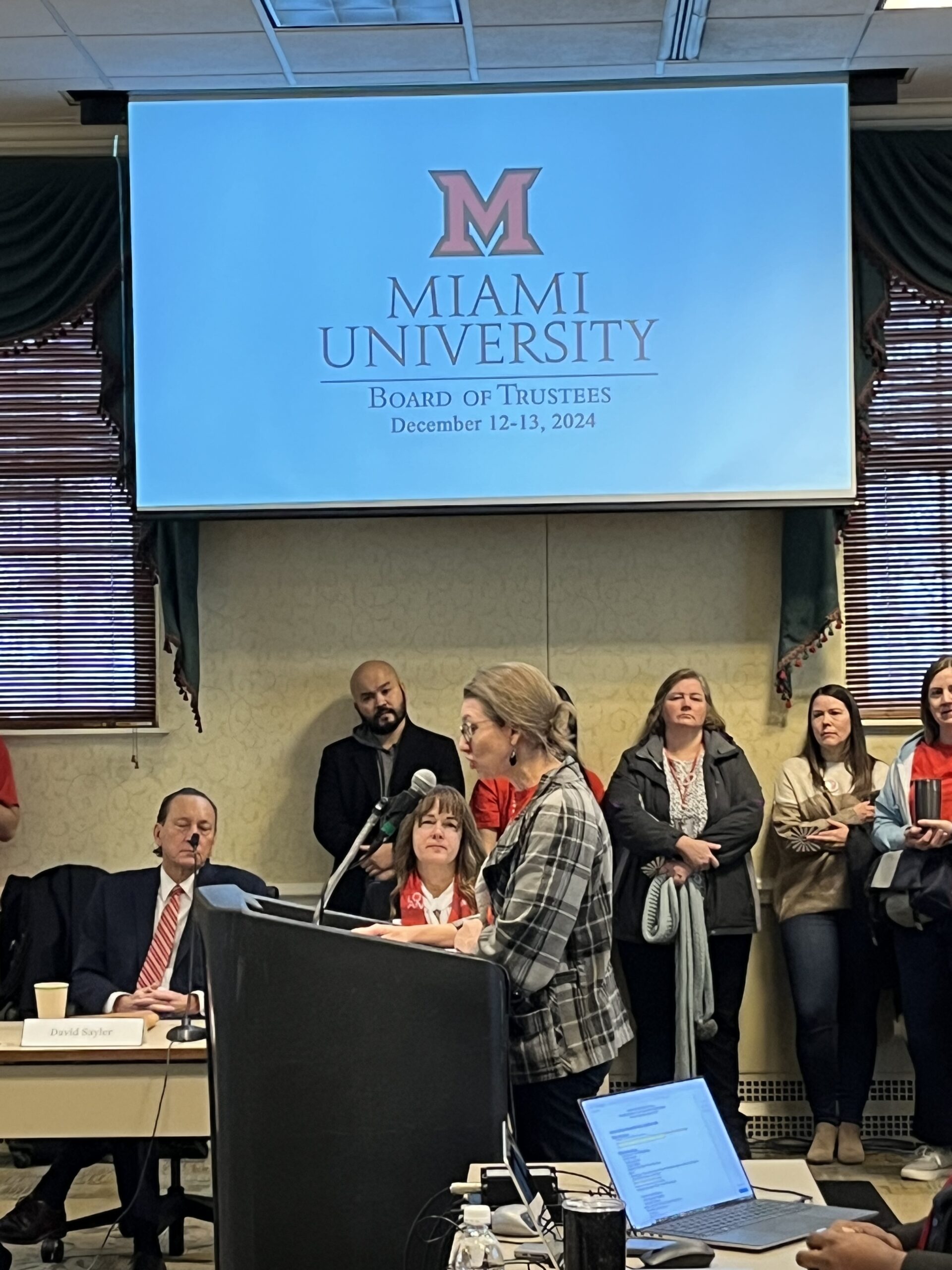

At the Board of Trustees meeting on December 13, History/Global and Intercultural Studies professor Elena Jackson Albarrán spoke on Miami’s new workload norms and the danger they present for preserving quality teaching and research at Miami.

For more on FAM’s direct action at the Board meeting and links to other speeches members made to the Board, click here.

My name is Elena Jackson Albarrán. I’m an Associate Professor jointly appointed in the Departments of History and of Global and Intercultural Studies, in which I am also assistant chair. I came to Miami in 2008, and although I had other job offers, Miami was unequivocally my first choice because of the engaged and compassionate students I met during my interview, and the demonstrated care taken by faculty and deans to cultivate a liberal arts experience. I am a CAS Distinguished Educator, and I was just awarded the top teaching prize in my field by the national organization the Conference on Latin American History. These honors are a direct testament to the unique teacher-scholar model fostered by Miami. But the new proposed workload policy is putting that teacher-scholar balance in peril.

The faculty and librarians before you today create the value upon which this institution has built its reputation. The new set of workload metrics inherited by our chairs in the past few weeks are part of an attempt to rationalize faculty labor. That system is premised on the assumption that teaching one 3-credit course takes 8 hours of work. So faculty in my department audited our hourly work over the course of five weeks, and found that the average amount of time we spend teaching one 3-credit course is 12-15 hours. The baseline unit of the workload metric is skewed.

I received a handwritten thank-you note from a student this week. Many of us did. I love these. It says, in part: “This was my first time in a college history class, and wow, it blew me away. I really appreciate the passion you brought to the class, it is clear you care a lot about it and it really makes a difference.”

I think the Board of Trustees, the administrators, and the faculty share common goals. We all want Miami to continue to be a place that students want to study and faculty want to work. We want to preserve Miami’s exceptional reputation as a leading public liberal arts institution. We also share a desire for work equity. We would all be happy to improve on the workload models to ensure that everyone contributes equally to the academic mission and is compensated commensurate with that work.

But a literal application of the current workload metric as it stands would radically destabilize the educational ecosystem that we have now. A more tempered, sensitive model needs to be developed in collaboration with faculty as part of shared governance. We know best how our time is allocated, where our research is disseminated, and what preparation we need to continue to mentor our students for life after Miami.

Our students are getting jobs–by Miami’s Outcomes data, 99% of 2022 graduates found employment or graduate school placement, and mid-career Miami alums were making $132,000—a 46% increase over my own mid-career salary. They are getting these jobs because we are preparing them. We are generating that value. The return on that investment comes back to us in thank-you notes, not salary increments. And we’ve sustained that way for some time.

But simultaneously raising our teaching loads and demanding more research output will guarantee diminishing returns on Miami’s long tradition of excellence in undergraduate education. Today, we urge you to recognize the value that we generate. The student-faculty relationships that we build behind the brick walls and in the iconic green spaces of this campus do not deteriorate in value like physical facilities do—they create the conditions for lifelong learning and the building blocks for future careers.

Leave a Reply